Gastarbeiter 2.0

9.4.2012 by ramon bauer

German politicians – from Angela Merkel downwards – encourage young and skilled people from crisis-hit countries with high unemployment like Spain and Greece to move to Germany in order to mitigate its skilled labour shortage.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Gastarbeiter (guest workers) from Southern European countries (like Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal and the former Yugoslavia) as well as Turkey poured into Germany to fill the jobs that Germans didn’t want. After the German reunification, unemployment was on the rise and reached record highs by the late 1990s. The direction of labour migration seemed to be reversed, as thousands of young and skilled Germans started to look for jobs elsewhere in Europe (especially in the Netherlands, Scandinavia, Austria and Switzerland). But Germany’s economy recuperated and unemployment is constantly decreasing since 2005, seemingly unimpressed by the global economic and labour market crises. In 2011, more people in Germany were in employment than ever before and unemployment rate settled in the single digits. While many European economies and labour markets are facing doom and gloom, Germany is booming – and is confronted with a shortage of workers.

Contrary to the labour market demands of the 1960s, as full employment lead to a shortage of unskilled workers in low-wage sectors, nowadays German companies are struggling to find enough skilled workers. Although low-wage employment accounts for more than 20 per cent – compared to only 13.5 per cent in Greece and 15.7 per cent in Spain (according to OECD figures) – this sector is quite saturated due to the Agenda 2010 labour market reforms that were initiated by the late Schröder government in 2003. The well-intended aim of the reforms to get the poorly-qualified and long-term unemployed back into the workforce, must be also associated to what Sarah Marsh and Holger Hansen calls the “The Dark Side of Germany’s Jobs Miracle”, as explained by in a recent Reuter’s article (8 Feb 2012):

Job growth in Germany has been especially strong for low wage and temporary agency employment because of deregulation and the promotion of flexible, low-income, state-subsidised so-called “mini-jobs”. (…) The number of full-time workers on low wages – sometimes defined as less than two thirds of middle income – rose by 13.5 percent to 4.3 million between 2005 and 2010, three times faster than other employment, according to the Labour Office.

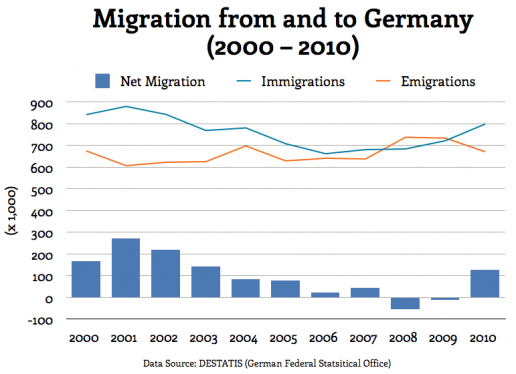

Since more than a generation, Germany’s demography is caught in a low-fertility trap that hardly can be compensated by immigration, thus the population is not only ageing but is actually already shrinking. Due to this demographic momentum, the German workforce potential might decline by around 6.5 million until 2025 (as estimated by the Federal Employment Agency in 2011), if immigration does not increase significantly. However, during 2008 and 2009 – and for the first time in decades – more people left Germany than arrived there, but net migration turned positive again in 2010 (see chart below). Beyond quantity, it is also the qualitative aspect of immigration that counts in order to cope with the chronic demand of the German industry for skilled labour. While many young and especially highly educated left Germany behind during the last decade (and still do so), new and existing programs and initiatives that promote skilled immigration to Germany did not pay off yet.

Only recently, German politicians became quite pro-active in their attempt to kick-off skilled immigration. In February 2012, on a visit to Madrid, German Chancellor Angelika Merkel encouraged young and skilled Spaniards to escape unemployment by getting a job in Germany – and, by doing so, prompted a rush on German courses in many Spanish cities. Following Merkel’s strong hint, Germany’s Employment Agency organized first job fairs in countries like Portugal, hunting skilled labour for short-staffed companies back home. Ursula von der Leyen, Germany’s minister for employment, wrapped up these recent efforts into a political win-win situation: “Germany’s economy plays its part in combating the unemployment crisis in hard-hit Southern European countries”.

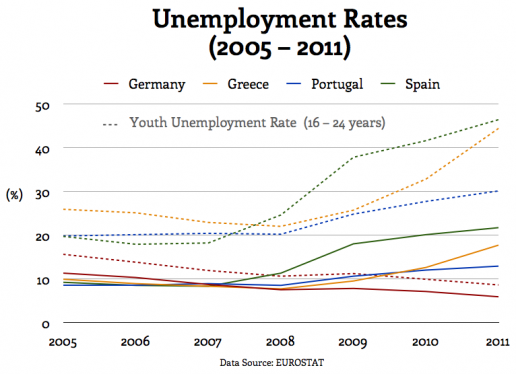

One has to agree with the German ladies when looking at the evidence of diverging trends in unemployment across Europe. While unemployment is persistently decreasing in Germany, it is on the rise in many other countries. In fact, unemployment rates even more than doubled in countries like Greece, Spain and Portugal since Lehman Brothers closed their doors in 2008, reaching more than 20 per cent in Spain and Greece and around 15 per cent in Portugal (by Feb 2012). Even more dramatically, the youth unemployment rate (for people aged 16 to 24 years) also doubled in many countries and broke through the 50 per cent barrier by early 2012, while youth unemployment in Germany decreased below ten per cent during the same period. Moreover, the unemployment rate for higher (tertiary) educated rests below three per cent in Germany, while the rate for lower educated (with only compulsory education or less) is six times higher. Educational differences in unemployment are significantly smaller in Spain and Portugal (times 2.5) and nearly non-existent in Greece.

Taking these disparities into account it appears quite rational, if those young and often well-educated, but unemployed people in economically hard-hit countries of Southern (and also Eastern) Europe would take advantage of the common European labour-market, which is open to all citizens of (most) EU Member States. Institutions like EURES – the European Job Mobility Portal and other initiatives like joint job fairs will help to channel regional and local labour demands and supplies, and – let’s think “win-win – enable young Europeans to escape local unemployment while supplying the urgently needed labour to the drivers of the European economy like the buzzing German Wirtschaftsmotor.

Like Germany, also other intact and prospering economies and labour markets are first and foremost looking for skilled labour. New labour migration flows from Southern Europe will differ strongly from the generation of Gastarbeiter in the 1960s and 1970s. Gastarbeiter 2.0, although originating from the same geographical regions, will be much more educated than previous waves of labour migrants. As a consequence, this new generation of immigrants might, on the one side, integrate much more smoothly into the host societies, when compared to their predecessors. On the other side, this human capital will be badly missed in Spain, Portugal or Greece, when these economies will (try to) regain their stability one day.

It remains to be seen, if such a migration dynamic will turn out to be a brain drain in the longer term, or rather a win-win situation as outlined by Frau von der Leyen; or even a win-win-win situation, if the generation Gastarbeiter 2.0 will circulate back to their places of origin, whenever their skills are needed back home. Since unemployment is still rising almost everywhere in Southern Europe for the fourth year in a row, more and more young and skilled people will depart Greece, Spain, Portugal and Italy to more promising destinations like Germany. For those concerned, the European labour market – granting EU nationals the right to full mobility between the Member States – is a great opportunity to escape unemployment and the lack of prospects at home, by looking for a better bid somewhere else in Europe. However, a new wave of emigration will not resolve the crisis in those EU countries affected, but it could at least improve the individual prospects of many EU citizens.

No comments. Would you like to leave a comment here?